A Game of Musical Chairs Over Hot Coals

There's a common belief that people who don't have jobs somehow just aren't trying hard enough, and this belief is therefore based on the idea that there are enough jobs for everyone. To get a job, all one really needs to do is just try hard enough.

"Just go get a job."

The Harsh Reality of Jobland

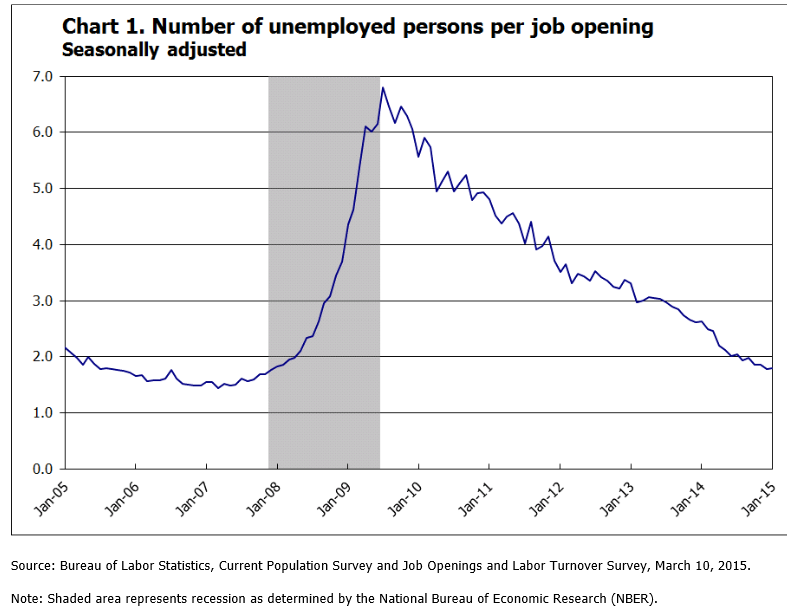

Source: BLS

The number of unemployed people per job opening varies by year, but it is never 1 to 1. In mid 2009 it was 7 to 1, meaning there were seven unemployed people for every one job opening. Today we hear how great the job market is and there's still two unemployed people for every job opening. We must also keep in mind that those who have dropped out of the labor market entirely - as in they've given up looking for a job - means they aren't actually even counted anymore as unemployed even though they are not employed. So there are actually more than two people for every one job right now. It's just that some are waiting for more and better jobs to open up before they bother to start looking.

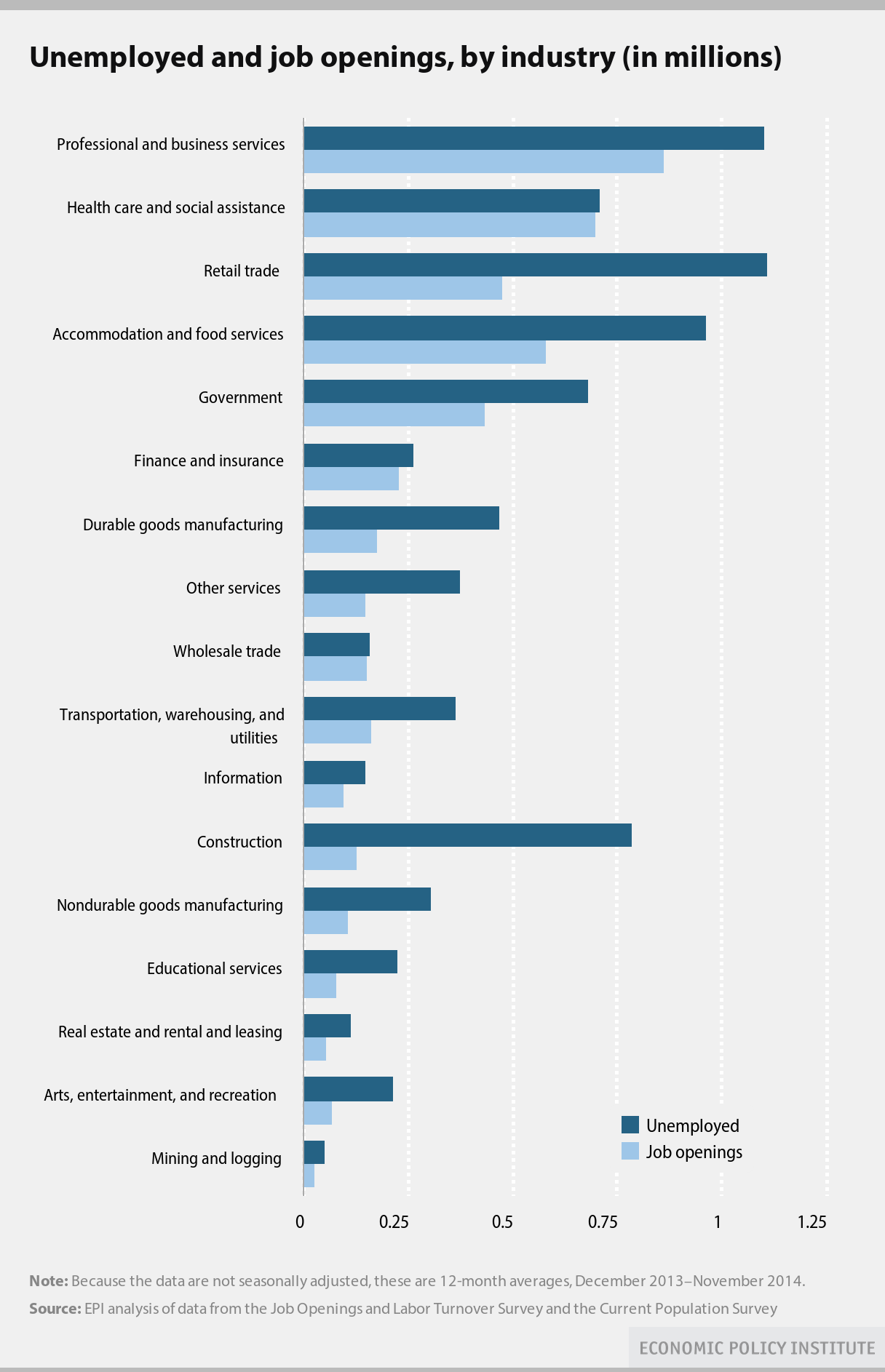

For those who are aware of this perpetual job shortage, there is then a belief that if we only break apart the data, and look at unemployment by job sector, we'll see that those who are unemployed are actually just "fools" who went to art school, instead of "wise" STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) degree holders. So let's take a look.

Source: EPI

As we can see, there are more unemployed people than jobs available across each sector of the job market, even including health care, and that one's considered practically a slam dunk at this point in terms of finding employment.

There are simply not enough jobs for everyone to have a job all at the same time.

Doesn't this sound kind of familiar? This idea that we walk around and around looking for something along with others looking for the same thing, only to find that some, and possibly even us, must in the end be excluded from what we seek?

It sounds like a game we all played as kids...

The job market is actually a game of musical chairs.

There is however a key difference between a game of musical chairs and the way our job market works, and that's that when the music stops in musical chairs, the winner is sitting while the loser is just left standing. But because the only way to gain access to the resources we need to survive is through the earning of income, those unable to earn an income aren't just left standing. They are left in poverty. And poverty hurts.

So now let's imagine a game of musical chairs played on a hot bed of coals. There are 10 people and 5 chairs, the same ratio as exists right now in 2015. Everyone is hopping around trying not to get burned, when the music stops. Five people are rewarded with security from pain, and five people begin to burn.

Let's look closer at these five burning people. Can we say anything about them in regards to ability or education knowing what we know about job scarcity? Can we truthfully say that all five sitting are the ones who rightfully deserve to sit, and all those standing rightfully deserve to burn? Has luck played no role in this?

According to Matt Bruenig writing for Demos using Census data, 1/3 of people experience poverty in any given year, and over the course of three years only 3.5% experience it the whole time. Looking at our entire working lifetimes, 40% of us will at some point live in poverty for a full year. Is this because four out of every ten people somehow deserve it?

This data instead appears to point to a large degree of luck in sitting or standing, with only around 3% of people having some kind of personal inability to find a chair. So at the absolute most, if we choose to view poverty as being somehow a matter of personal choice, only 3% can even potentially fit this description. For the other 97%, it's really just a matter of when the music stops.

Now let's look closer at the chairs themselves. We want to assume that if we are sitting, our feet are no longer burning and that we're entirely safe from the hot coals. But that's not actually the case. Some of the people sitting actually burn too.

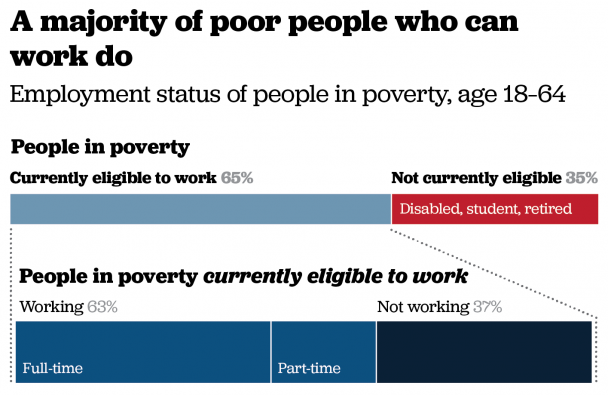

Source: EPI

For every three people in poverty who are eligible to work, two are working. So, having a job does not prevent poverty. Or in other words, being fortunate enough to successfully grab a chair does not mean our feet are out of the coals.

So not only are people being punished for being unlucky when the music stops, but so are some of the people lucky enough to grab a chair. Does this make any sense at all? Does this sound like a fun game with fair rules? If not, why are we playing it?

I say it's high time we change the rules.

Here's how we can do it, and also why we have to do it.

Thanks to technology, there are going to be fewer and fewer chairs as the music plays on. The chairs themselves are going to offer less and less protection from the hot coals, and we'll never really know how good of a chair we're sitting in until our feet start burning. So here's what we do...

We build a concrete floor a few inches over the coals with a universal basic income.

With basic income, no matter what, no one's feet will burn. No matter whether you are sitting or standing, no more burning for anyone. This also doesn't mean that no one will play the game anymore. Don't we usually play musical chairs over an actual floor instead of hot coals? In fact, looking at it this way, doesn't it now seem kind of sadistic to not already be playing this particular game with a concrete floor instead of hot coals?

With basic income, the music will still start and stop. Some people will still get to enjoy sitting while others are still left standing, but no one will burn. No matter how many chairs are removed from the game, no one will burn.

So what effect will this have? Will all that not burning make people lazy? Do we need coals to motivate us?

Not according to what we newly know about safety nets. Their existence actually provides greater motivation.

Take food stamps. Conservatives have long argued that they breed dependence on government. In a 2014 paper, Olds examined the link between entrepreneurship and food stamps, and found that the expansion of the program in some states in the early 2000s increased the chance that newly eligible households would own an incorporated business by 16 percent. (Incorporated firms are a better proxy for job-creating startups than unincorporated ones.)

Interestingly, most of these new entrepreneurs didn’t actually enroll in the food stamp program. It seems that expanding the availability of food stamps increased business formation by making it less risky for entrepreneurs to strike out on their own. Simply knowing that they could fall back on food stamps if their venture failed was enough to make them more likely to take risks.

Just knowing food stamps existed as an option, encouraged people to take the risk to start their own businesses. This is also the same reason Denmark has year after year been considered the best place for business.

One of the keys to Denmark’s pro-business climate is the flexible labor market known as “Flexisecurity,” where companies can easily hire and fire workers with out-of-work adults eligible for significant unemployment benefits. Unemployed workers are also eligible for training programs. It creates one of the most productive workforces in Europe. “The model encourages economic efficiency where employees end up in the job they are best suited for,” says Weis. “It allows employers to quickly change and reallocate resources in the workplace.” Denmark is one of the most entrepreneurial countries in the world.

So in Denmark, we see a game of musical chairs being played where people are encouraged to stand up from one chair and go sit in another. Chair owners can even more easily dump people out of chairs or get rid of them when no longer needed. People standing can take their time finding new chairs, and the result is a country full of people not only finding chairs they like (which is great for productivity), but making new ones and destroying old ones, all with little if any burning.

It should also be no surprise that playing musical chairs on something other than coals actually leads to greater happiness, even in the midst of disappearing chairs.

When the researchers control for various factors like the unemployment rate, they find that happiness of people experiencing job destruction is higher in states with more generous unemployment benefits and lower in states with stingier benefits. This is likely because people are less worried about the job-destroying effects of technological change when there is a social safety net they can count on.

A feeling of security makes all the difference. Basic income provides that security in the most efficient and universal way possible, where everyone is guaranteed the same minimum level of opportunity with maximum freedom of choice.

Even F.A. Hayek, a Nobel prize-winning economist considered far to the right of center with his advocacy of free markets for free societies, believed a minimum income made sense as a means of "limited security"through the assurance by government of minimal sustenance.

There is then the important issue of security, of protection against risks common to all, where government can often either reduce these risks or assist people to provide against them. Here, however, an important distinction has to be drawn between two conceptions of security: a limited security which can be achieved for all and which is, therefore, no privilege, and absolute security, which in a free society cannot be achieved for all. The first of these is security against severe physical privation, the assurance of a given minimum of sustenance for all; and the second is the assurance of a given standard of life.

Basic income does not mean everyone earns the same amount of money. It means everyone starts with the same amount of money. It is a guarantee of opportunity, not of outcome.

Few would suggest a game of Monopoly where no one has a minimum amount with which to start playing. It makes no sense to start Monopoly with $0. Why not just make it so that we all as citizens start each month with $1,000 instead of $0? Then all income earned from our labor can be earned on top of our basic income. Some will use it to earn much more than others, but no one will start with less.

We can do a lot more with something than we can with nothing.

In Namibia, when given basic incomes, self-employment jumped 301%.

In Liberia, when given basic incomes, 1/3 of recipients started their own businesses.

In India, when given basic incomes, recipients were twice as likely to increase their productive work as those in control villages.

In Kenya, when poor people were given cash unconditionally, 90% of them used it to start their own businesses or purchase livestock.

When people have a minimum amount of money to start with, they use it to enable work. They use it to earn more money, or to pursue unpaid work they wish to pursue, like being a parent instead of paying someone else to be a parent for them. They also use it to pursue education. Students focus on school and even get better grades.

Giving everyone the same basic amount of cash - a basic income - is how we change the rules to make our fiery game of musical chairs work better for everyone through the creation of a room temperature protective floor.

Or we can just continue burning together, and watch as our machines begin sitting in the chairs themselves...

It's our choice.

This post inspired the creation of a video that took years to animate. It was created by adamanimates and is available on his channel in both US and Canada versions.

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.