Guess What Happened When Liberia Tested a Pilot Program of Cash Transfers to the Extreme Poor in Bomi

I'm always on the lookout for more scientific evidence of what happens when people are provided cash incomes unconditionally. Recently I found something new, a pilot program tested in Bomi and Maryland Counties in Liberia that started in 2009 and ended in late 2014. Implemented by the Liberian Ministry of Gender and Development with support from UNICEF and funded by the EU and Japan, it was called the "Social Cash Transfer Programme (SCT)" and was aimed at the "ultra-poor" - the poorest of the poor.

A final study remains to be completed and published, but the Center for Global Health and Development (CGHD) at Boston University did do a study of the results halfway through. What they found actually closely matches the evidence we see from basic income experiments and other cash transfer programs elsewhere. It's hard to deny real observed results of what happens when people are given cash without conditions. We can debate hypotheticals all day long, but it's actual results that speak for themselves.

So what was observed in Bomi? Did the poor spend all their money on alcohol? Did they gamble it away? Did businesses fail? Did school attendance decrease? Did overall health decline? Did cats begin living with dogs?

Summary of Results

The study found compelling evidence that the SCT program improved the food security, health, education and economic conditions of participating households. Cash transfer program households reported improved food intake and larger food stores that lasted longer. When faced with illnesses they were more likely than in previous years to seek healthcare for all members of the family, especially children. School attendance improved and 66% of children had improved school marks. Participating households also generally reported improved economic statuses. Indeed, two-thirds of the heads of program households reported satisfaction with their quality of life, compared to just 20% of a comparison population. The study also found evidence of multiplier effects that enable the benefits of the SCT program to reach beyond the immediate beneficiaries to the community at large.

Thus the evidence Bomi provides is in further support of the evidence we already have. As is observed repeatedly, when cash is given to the poor, they use it as most anyone else would use it: for food, school, housing, health, savings, clothing, household items, etc. Without being forced, they make decisions they feel are best for them and their families, and the results are remarkable compared to similarly poor control groups who don't receive unconditional cash.

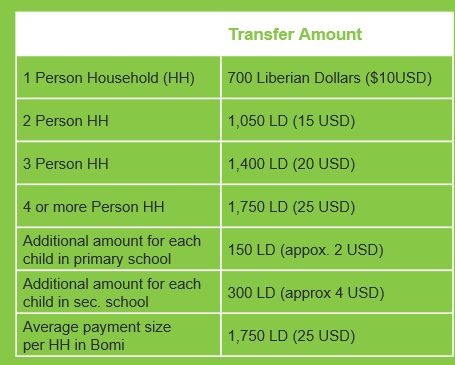

So how much cash was involved in the Liberia SCTs?

The Cash Received in Bomi

These payouts might seem small, but they were regularly dispersed over the course of each year, and actually relatively high. How high? A one-person household got 700 Liberian dollars ($10 USD) per transfer. Each additional person resulted in an extra 350 LD ($5 USD) up to a maximum of four people. A bonus was given on top of this for each and every kid in school (unlike conditional programs where school is required to receive anything). The result was an average household amount per transfer of 1,750 LD ($25 USD).

To get an idea of the relative size of this amount, the payments were intended to bridge the gap between what the poorest had to spend, and the national average standard of living in Liberia as measured by their per capita GDP of 15,825 Liberian dollars ($211 USD).

So, relatively speaking, this is no small amount. As one comparison, it was very similar to the payments in the Namibia Basic Income Guarantee Pilot, where every Namibian under 60 got 100 Namibian dollars per month (727 LD or $9 USD) as a basic income. So the payment amounts in Namibia and Liberia were basically the same, it's just that in Namibia, it went to everyone not already covered and not just the poorest.

As another comparison, if we were to test a similar pilot program in the United States as in Bomi, it would be like bridging the gap between the poorest 8% of Detroit and the US per capita GDP of $53,000 by guaranteeing all pilot participants an income floor of around $1,000 per week, and comparing how well they did with those equally poor who weren't included in the pilot. (Note: I'm actually not the first to suggest a basic income pilot be carried out in Detroit. See: Venture Capitalist Albert Wenger.)

Essentially, in Bomi an income floor was created at the national average. Try to imagine an income guarantee of that size, in essence guaranteeing you your share of the country's total productivity; basically the same share we used to have but lost when productivity decoupled from wages decades ago.

So how was all this money spent?

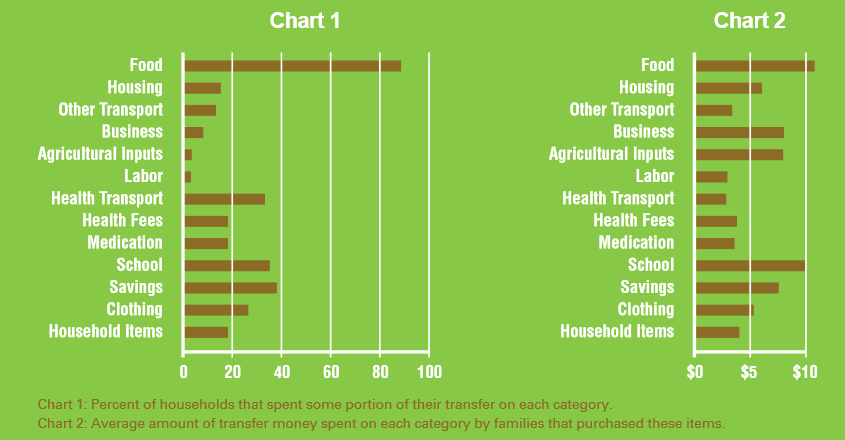

Surprise surprise... it was food. It was spent mostly on food. Also, other basic needs.

The Purchases in Bomi

The main categories of transfer spending were food, savings, education, clothing and healthcare. Almost every household (88%) used their transfer to purchase food, which was also the item on which recipients spent the most money. Indeed, households who purchased food with their transfer spent, on average, LD$750 on it. The next two most common expenditures were savings and education. Households that purchased these goods/services spent an average of LD$528 and LD$694 respectively. While families saved for many different reasons, reports from the field indicate that a large portion went into longer term home repairs (such as the upgrading of a roof) and small business development. Other spending categories of note include agricultural inputs and businesses. While the number of families that purchased these items was limited, those that invested, invested significantly. This suggests a commitment to small businesses and agricultural production for families ready to make that leap.

We hear over and over again that the poor just can't handle money, and that the more poor someone is, the more true this is. And yet here we have the ultra-poor in a relatively poor nation, spending the cash given to them on food, savings, education, health care, and even entrepreneurship. A whopping one third of pilot participants reported starting their own businesses. And these new businesses along with existing businesses did well, because what these transfers also created were consumers.

The clear majority of program households (65%) reported an improved economic situation over the past year... Because 93% of the transfer money was spent within Bomi County, the impact of the program was felt beyond the immediate beneficiaries. Business owners reported that they were coming to rely on SCT recipients as important customers. Seventy-five per cent of business owners noticed positive impacts on their businesses. They attributed 20-50% of their growth to the SCT program. A number of program households reported even more direct forms of spill-over effects – 19% shared money and 48% shared food. Interviews also found that program households directly supported their neighbors in times of serious healthcare needs. Those that started businesses were also able to contribute to the broader local economy by offering new and improved goods and services.

Not only did new businesses start, and old businesses thrive, but people also even used their increased incomes to directly help each other. About a fifth of the pilot participants shared their money with others, and about half of them shared the food they purchased with others.

What else happened?

The Effects in Bomi

While 74% of non-pilot participants experienced worsened food insecurity, 90% of those in the pilot experienced improved food security.

Pilot children were less likely to miss school, and two-thirds of them received higher grades. These results were also due to kids no longer being forced to work. (Note: Similar experimental results have been observed in Manitoba and in Gary, Indiana, rural North Carolina, and rural Iowa).

Half of pilot participants reported an improved housing situation, versus only 12% of those who weren't included in the program. And 76% reported being happy with their home, versus 17% for non-participants.

65% of those in the pilot reported being happy with their lives, while only 19% of those not in the pilot reported the same happiness.

Pilot participants were about two times more likely than non-participants to seek medical care when needed, both for themselves and their children, and both adults and children alike were also twice as likely to have improved health.

“From where I sit as a health worker, I can with no doubt say that the impact on health is there and it is great.”—Bomi County Community Health Worker

These results are not trivial. They are transformative. They are transformative to the point $5.1 million in funding from the World Bank for more cash transfers has already been secured for six more counties in Liberia.

We can claim that because this pilot took place in Liberia, there is nothing to learn from the results, but that would be pretending that human beings are different on a fundamental basic needs level. It would be pretending that although the poor in less developed nations are certainly likely to spend cash on food and school and small business creation and consumption, Americans are far more likely to starve in the streets while methed-out clutching brand new iPads.

Human behavior is human behavior. Observations made from cash transfer programs in country after country continue to report the same general results. People spend their money on food that even involves more fruits and vegetables. People spend their money on new homes and improving their homes. People invest their cash as capital to start new businesses. Students focus on school. Parents focus on kids. Communities focus on each other.

These are the effects of unconditional cash transfers. These are the effects of people being given some form of minimum income. How many times and in how many places do we need to observe these effects for us to believe they are representative of what happens when people are given money without conditions? At what point will we look back at today and wonder how we ever thought guaranteeing some form of minimum income was not a common sense idea? The sooner we reach that point the better, because the results are already in.

Basic income works.

Read the full 20-page UNICEF report in pdf format: Transformative Transfers: Evidence from Liberia's Social Cash Transfer Programme

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.