Breaking Down Without a Spare

America’s lopsided welfare system of counterproductive public assistance

The Parable

Let’s imagine we’re in a car together on a road trip. We’re on our way to visit your family. We’d have actually preferred to fly, but that route wasn’t in the budget, which is very limited. Times have been tough lately. Sometimes it feels like the economy is only working for everyone else. Fortunately, we have just enough gas money to get us to our destination.

And then our tire blows…

Moments later we’re on the side of the road. Unfortunately there’s no spare. We had no choice but to drive on it.

You call for some roadside assistance. After being on hold for a few hours and being transferred between multiple departments, you are eventually told a truck will be there soon to help. Twelve hours later, it does. A woman appears from behind the now open truck door.

“Hi. I’ll be your case adviser today. I’m here to help.”

She asks you about your driving history and my passenger history. She asks how often we drive together, and if we drive around with anyone else or have another driver in the backseat. She asks to search the trunk to make sure we’re not hiding any extra tires. She asks you why you didn’t just have another spare.

Car after car passes by. Hours turn to days. Finally we’re told everything is satisfactory and we will receive our assistance now. She goes back to her car, and pulls out what definitely does not look like a spare.

“I’m sure you can understand how we can’t just supply you an actual tire,” she says. You could drive anywhere on four tires. We will assist you though. Don’t worry. I’m here to help.”

Because an actual tire would apparently involve too much freedom, you are handed a voucher that can be used to exchange for an old flat tire in most (but not all) stores. You are also handed vouchers for tire sealant, rubber patches, an electric air compressor with the wrong adapter for the car we happen to be driving, and a balloon half full of air.

“So we’re not only not getting a spare tire, but you’re giving us a voucher we can’t actually use right here — where we actually are — for another flat tire that we’ll still need to fix ourselves along with the tools that won’t allow us to fix it, and air in a form we don’t need?”

She nods in a way you can only imagine she’s done before.

“How much does all this cost anyway?” you ask. “Oh, about $600." she says.

“How does that make more sense than spending $150 on a tire?” You then look at me and together we ask the same question.

“Isn’t there a better way than this?”

The Reality

The above parable is of course fictional, but the reality it represents is unfortunately not.

Here in America, we like to think we have a safety net. We like to think we take great care of those in need. In fact, people like to believe it so much, we actually kid ourselves into thinking it’s a kind of safety hammock, where people with an aversion to hard work and gumption lie back and peacefully sleep their days away in a perpetual state of welfare nirvana next to surfboards covered in lobster and caviar.

But is that really the case?

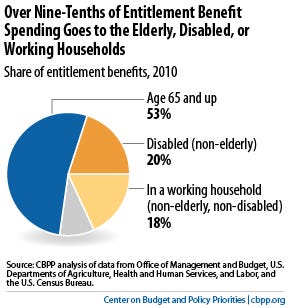

A new CBPP analysis of budget and Census data, however, shows that more than 90 percent of the benefit dollars that entitlement and other mandatory programs spend go to assist people who are elderly, seriously disabled, or members of working households — not to able-bodied, working-age Americans who choose not to work.

That’s right. Nine out of ten people are people that can never be claimed as sitting in hammocks on easy street. These are kids like you once were. These are grandparents like your own grandparents. These are people working their asses off in jobs that aren’t paying them sufficient enough wages to not require any help.

These are the people on the side of the road with a flat tire and no spare.

And how often does this happen? How many people end up on the side of the road at some point in their lives?

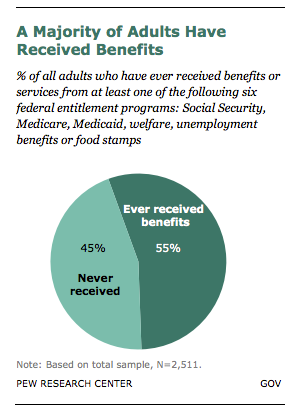

Pew Research Center finds that a majority of Americans (55%) have received government benefits from at least one of the six best-known federal entitlement programs. The survey also finds that most Democrats (60%) and Republicans (52%) say they have benefited from a major entitlement program at some point in their lives. So have nearly equal shares of self-identifying conservatives (57%), liberals (53%) and moderates (53%).

That’s right. More people have received benefits than not received them. In other words, flip a coin. You are more likely to end up on the side of the road than you are to see heads or tails. Needing help is not a matter of if. It is only a matter of when. Even people with PhDs aren’t immune to this.

And when you do need that help, how do you want it given to you? Do you want it to look like the above fictional account of our road trip gone wrong? Do you want those helping you to spend $4 to give you the equivalent of $1? Do you want your help to involve needless work, vouchers with strings, and stuff you can’t even use, or do you just want to get back on the road?

All of that is exactly what we have right now.

- Our safety nets are full of needless bureaucracy.

The first step in the food-stamp application process was turning in every imaginable document regarding my identity, housing, assets and personal finances. I was photographed and fingerprinted, which made me feel like everyone thought I was a criminal. After winding my way through the byzantine bureaucracy, including several hours-long appointments during which I obviously couldn’t be looking for work, I was finally approved; the monthly allotment worked out to about $5 per day.

To keep receiving food stamp benefits, I had to spend every “work day” at a Human Resources Administration work-search office – my presence there was mandatory from Monday through Friday and from 9am to 5pm. The office was more than an hour from my apartment (that is, when public transportation – which I had to pay for myself – was functioning properly), but arriving even five minutes late earned a strike against my record for “non-compliance”.

Two strikes, and I would have been out: the US system automatically revokes all benefits for rule-breakers, who then have to start the application process all over again.

Would you give someone a loan and then force them to attend classes 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, to teach them how to pay back the loan, instead of letting them use those 40 hours per week to actually pay back the loan? Does this make good sense?

2. Our safety nets cost far more than just giving people the money required to help them, and this is true even in the best possible circumstances.

Masters degree-level social workers, with tiny caseloads, delivered intensive personalized services, including home visits, to a group of welfare recipients, including a batch of extremely hard to employ single mothers. They attempted to get the women into the workforce and self-sufficient for the long haul.

The program produced better results than any such program ever had. Almost half of the study participants went to work for at least a year, double the rate of the group without the individualized attention, and their earnings increased significantly. The clients who got the individual casework were less depressed, less likely to lose custody of a child, and more likely to receive child support. But they still faced food and housing hardship; they were still poor, if working poor. And again, only half the study participants went to work.

Providing all those individualized services cost the state $8,300 per client — so much that researchers who evaluated the program concluded that the “benefits to society did not outweigh its costs during the study.”

… The families might have been ended up in a slightly better place, at least for a while, but the state of Nebraska would have been better off writing them a $5,000 check and calling it a day.

If we spend $8,300 for someone to be just as well off as just giving them $5,000 cash, why should we continue wasting $3,300 per person? Does this make good sense?

3. In 2006, the late Allen Sheahen looked at the list of 1,607 federal programs funded by the US government and calculated the number of tax loopholes we could close and which programs for the poor we could consolidate into a single refundable tax credit. Here’s what he found:

The income tax system is too complex with 138 separate tax loopholes. The welfare system is equally complex with more than 200 separate programs to help the poor.

Do we really need all of these programs and loopholes? Is that level of paternalism and inefficiency truly what’s best for us?

Instead of all 200 different programs for the poor, let’s just take a closer look at a handful of the biggest ones. We currently spend about $300 billion dollars on seven different programs that are essentially cash or easily replaced by it (EITC, CTC, SSI, TANF, SNAP, WIC, and Housing Assistance) on around 50 million people living below the poverty line. That’s an average of $6,000 per person, and yet instead of cash we insist on benefits in kind despite 84% of economists disagreeing with that strategy over cash. Even if the overhead is only 5%, that’s five billion dollars wasted for every hundred billion spent, or enough money to instead just give $6,000 to 2.5 million more people, without spending a penny more than we already do.

Meanwhile, what if you need $500 for rent and $100 for food, but are given a housing voucher for $400 and a food voucher for $200? You’ve been given just the right amount, and yet you’re $200 short because of being given vouchers instead of cash. And what if there’s no voucher at all for what you need that only costs $50? A $500 voucher wouldn’t help you, except through selling it to someone else who it could help. This is also why we can’t actually stop anyone from using vouchers for goods and services we don’t want them to have, and why we sometimes seek refunds for gifts after holidays. It’s the entire reason we invented money in the first place — efficiency of exchange.

Money can be exchanged for anything. Everything else has limits.

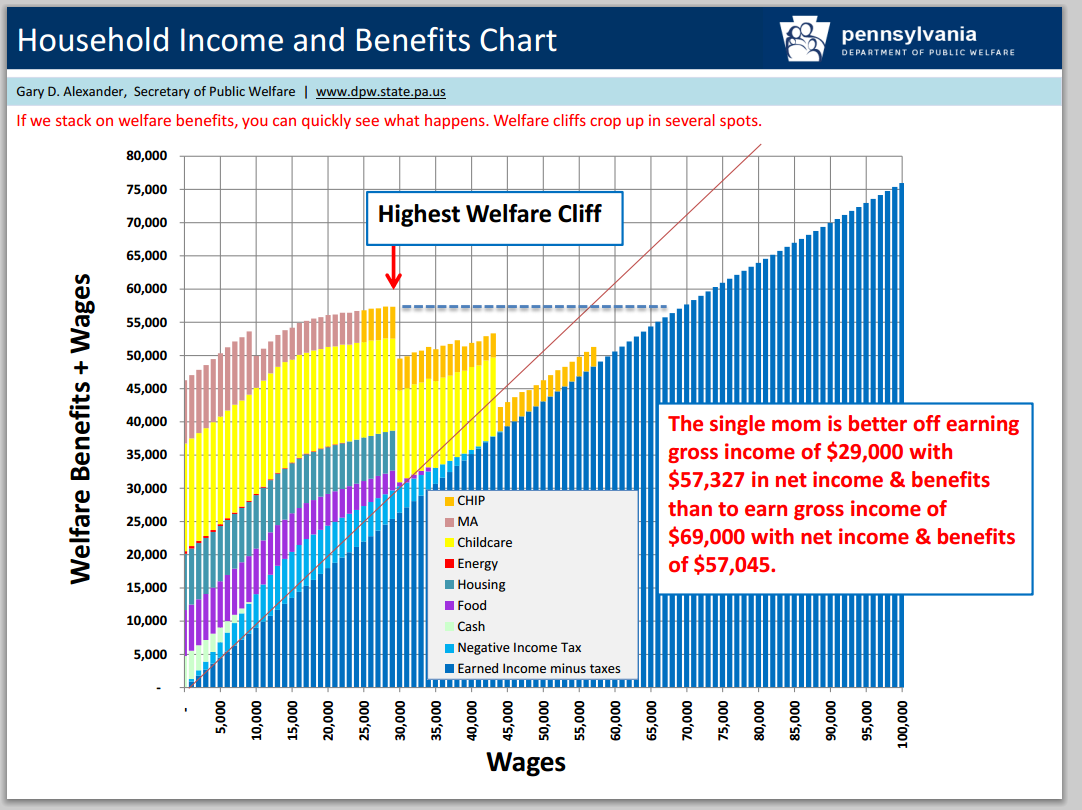

4. Finally, the worst part of all about our current flawed welfare system is the welfare trap it creates by pulling assistance away with increased earnings from labor market income. This loss of benefits can be so extreme so as to result in “welfare cliffs”.

Notice in the above slide, how someone earning $29,000 has the incentive to not earn more than that, through more hours, or a better job, or a raise, because earning $30,000 (just $1,000 more) would result in the loss of $8,000 in food and housing assistance, leaving them worse off. Notice too the nature of the help. Food and housing are necessities. That’s $8,000 that still needs to be spent, unless she keeps the job but opts for living on the street and eating out of dumpsters to avoid spending it.

Another cliff exists at $43,000 where someone has the incentive to not earn $44,000 (just $1,000 more), because that would result in the loss of about $13,000 in childcare assistance. Again, notice the nature of that loss. How can she keep the job that gave her a raise, if she’s no longer able to afford daycare so that she can go to work instead of watching her kid(s)? That’s a cliff that can force her to quit her job and find one that pays less, in order to get that assistance back. Is that the result we seek?

In case this is all too abstract, here’s a working mother in this exact situation:

“A system that works against the system’s own interests… it’s just so counterproductive.”

Our current system is not productive. It is not the fully functional safety net we need, especially as technology increasingly disrupts our day to day lives. If one day we can be a driver for Uber, and the next day Uber can buy a fleet of self-driving cars and fire all of us, that’s a world where we need a real safety net that doesn’t just drop away. We need more than a safety net. We need a floor set above the poverty level, so that regardless of any amount of disruption, we are still allowed to stand on our own two feet and start climbing again.

Don’t catch us and trap us with nets. We need a solid foundation that allows all of us a space in which to build our futures.

We also need to understand that those at the bottom aren’t the only ones receiving welfare. There exists a great deal of netting underneath the feet of all of us. We just don’t see it. It is the invisible safety net, lacking in any stigma.

“…the U.S. Government spent $24 billion on public housing and rental subsidies for the poor. But in that same year, it spent $72 billion in home ownership subsidies for the middle classes and the wealthy.”

Welfare for the Wealthier

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, when it comes to entitlement benefits, it is false to think those at the bottom receive most of the benefits. To the contrary, entitlement benefits are shared surprisingly proportionately according to population. Is this widely known? Do we talk about how our entitlement benefits are mostly distributed evenly to everyone?

Meanwhile, if we look at individual tax expenditures, it is the wealthy who represent a smaller percentage of the population and yet receive a disproportionately high percentage of total tax expenditures. Is this widely known? Do we talk about how the richest fifth of the country receives two-thirds of all tax expenditures or how the top 1% receives one quarter of it?

What exactly are some examples of this kind of welfare for the rich?

The Home Mortgage Interest Rate Deduction:

The most recent IRS data show few low- and middle-income taxpayers benefit from the home mortgage interest deduction. Those who filed tax returns with under $30,000 in adjusted gross income (AGI) in 2003 received just 9 percent of deductions for home mortgage interest, despite filing 52 percent of all tax returns. In contrast, 36 percent of home mortgage interest deductions were claimed by taxpayers with AGIs over $100,000.

This form of housing assistance is virtually identical to giving someone in poverty a housing voucher to help them afford a house, but instead they aren’t at all in poverty and we help them afford a nicer house (which is sometimes resold for a profit as soon as possible).

Over the past 20 years, more than 80 percent of the capital gains income realized in the United States has gone to 5 percent of the people; about half of all the capital gains have gone to the wealthiest 0.1 percent.

Warren Buffet has made this particular advantage famous in sharing how he pays a lower tax rate than his own secretary. Some would argue this lower rate for the rich is good for the poor, because it drives job creation, but is that really the case?

Jane Gravelle, a tax expert at the Congressional Research Service, says a rate cut could generate more government revenue for a year or two as investors take advantage of lower rates or a rising stock market, but she says that initial bump in tax revenue would fade. And the government, over time, would collect more overall if it kept the rate higher.

The fact that those few at the top are the ones earning the overwhelming majority of capital gains, and that those same people pay a lower tax rate on this income than anyone else, is undeniably a form of handout for the rich. It’s giving barrels full of money to those who already have trucks full of money.

Meanwhile, for billionaires who look upon those with trucks full of money as the relatively poor, we give them amounts of money so vast, it should be considered shocking.

The perfect example: Seven of every ten dollars spent to build CenturyLink Field in Seattle came from the taxpayers of Washington State, $390 million total. The owner, [billionaire] Paul Allen, pays the state $1 million per year in “rent” and collects most of the $200 million generated. If you are wondering how to become, like Allen, one of the richest humans on earth, negotiating such a lease would be a good start.

In New Orleans, taxpayers have bankrolled roughly a billion dollars to build then renovate the Superdome, which we are now supposed to call the Mercedes-Benz Superdome. Guess who gets nearly all the revenues generated by Saints games played in this building? If you guessed all those hard-working stiffs who paid a billion dollars, you would be wrong. If you guessed billionaire owner Tom Benson, you would be right. He also receives $6 million per annum from the state as an “inducement payment” to keep him from moving the team.

The common counterargument to facts like this, is to point out how much revenue it generates for the people of the city who publicly bankroll such massive private capital investments. The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City put an estimate on that value.

…The net present value of the jobs and tax benefits may be no more than $5 million from hosting an NBA or NHL team and no more than $10 million from hosting an NFL or MLB team. Even using the upper-bound estimates from the analysis above suggests that the public outlays on current sports facility projects far exceed any associated jobs and tax benefits.

In other words, taking New Orleans (my own city) as an example, it’s entirely reasonable to suggest that economically speaking, the value returned to the city in the form of taxes and jobs for building a billion dollar stadium for billionaire Tom Benson is about equivalent to what the city pays him every year just to provide him further incentive from ever leaving.

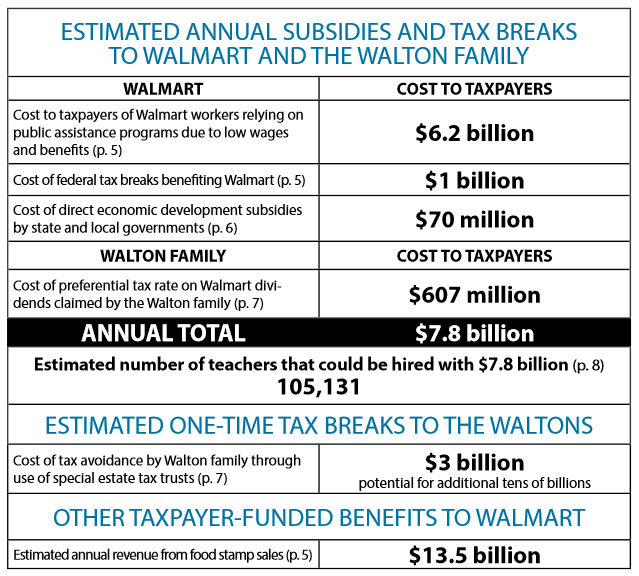

But that’s all still not the biggest example of welfare for the rich. Such an extreme example requires looking at the richest family on the entire planet — The Waltons of Walmart — who each earn more than $1.5 million per hour from their dividend checks alone and have a total net worth of $150 billion equal to about the bottom half of the entire United States. How much welfare do they get?

It has also been estimated, that if Walmart just raised their prices by merely 1.4 percent and put this added revenue into increased wages, their employees would no longer need welfare assistance, and therefore Walmart would no longer receive welfare assistance either. That they refuse to do this and instead choose to enjoy a free $8 billion or so a year, should make it clear they want to be on welfare.

But is that what the working Americans who work for them want?

Driving on Spares

It may have seemed a small detail and one possibly gone unnoticed, but it’s possibly the most important detail of all in our automotive parable.

“Unfortunately there’s no spare. We had no choice but to drive on it.”

It’s not that we made the unwise choice to go driving around without a spare tire. It’s that we could not make the wise choice, because our car had already suffered a previous blown tire and there was no money in the budget for a new one. After replacing our blown tire with our spare tire, we could only hope nothing else would happen until there was money for a new tire.

But something did happen. That’s the nature of unfortunate surprises.

It is this fact we must recognize, possibly above all. No one wants to suffer a flat tire, and no one wants to have no options but to call for help when we do get one. And we see this reflected in what we have done for decades now, as we have faithfully sought all possible avenues of increasing our incomes.

We went from one earner per household to two.

We asked for more hours and sought second, third, and even fourth jobs.

We got credit cards, took out second mortgages, and are now even tapping our own retirement funds.

It’s a small number that’s part of a much larger picture: The Internal Revenue Service collected $5.7 billion in 2011 from penalties, meaning that Americans took out about $57 billion from retirement funds before they were supposed to.

The median size of a 401(k) is $24,400 as of March 31, with people older than 55 having $65,300, according to Fidelity Investments. Those funds can disappear quickly in retirement, and the early withdrawals indicate that the coming retirement crisis could be even more acute than expected.

This is what it looks like for a country to be driving on its spare tire.

As citizens, we are doing everything we can. Some of us are even tragically dying in our attempts to struggle on, while over 10,000 others have already grown too tired of the struggle to even continue living. As long as wages continue to not rise, and as long as jobs continue to be eliminated due to advances in technology, we have nowhere else to turn but our own safety nets. It is for this reason, it will only become ever more increasingly important for us to look with open eyes and minds at our system of public assistance and how it functions for all of us, poor and rich alike.

If so many of us are already driving on our spare tires, and we recognize the road ahead is only going to get bumpier and more dangerous, then we must together make sure that we either make it quick and painless for us all to get right back on the road when we need assistance, or finally guarantee that no matter what, there will always be another spare tire for all of us.

Special thanks to Arjun Banker, Topher Hunt, Albert Wenger, Danielle Texeira, Paul Wicks, Robert F. Greene, Martin Jordo, Victor Lau, Shane Gordon, all my other funders for their support, and my amazing partner, Katie Smith.

Would you like to see your name here too?

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.