An Engineering Argument for Basic Income

This post is also available in Spanish and Czech due to the volunteer work of translators. Thank you to everyone who submits a translation for me to add here.

(Optional Audio: click here to listen to my narration of this article if you prefer listening to reading)

Before studying engineering, if someone asked me what 1+1 is, I would have said "2." Now, I'd say "I'm pretty sure it's 2, but we'd better make it 3 just to be safe."

I originally went to college at the Colorado School of Mines to become an engineer. I switched majors to psychology after two years, but I will always think of things from the perspective of engineering for the same reason I originally pursued it: what matters is reality and what works and doesn't work. I love math and I love science, but I really love how engineering takes math and science and applies them to make and improve real things. Being an engineer is about being a realist. It's about pragmatism over theory. It recognizes that the map is not the territory.

So here's one rule all engineers know, and it's Murphy's Law: Whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. Knowing that, failure therefore has to be a part of design. We don't want things to fail, but we know they will, because they always do, so what should be done?

The answer is fault tolerance.

In the event of component failure, a system should be designed to continue functioning either as normal, or at a reduced capacity. And when some system does fail entirely, it should be designed to return to 100% operating capacity quickly. Catastrophic failure should always be avoided, especially for mission critical systems, and even more especially when lives are at stake.

Think planes. If a single component fails, it shouldn't bring the entire plane down. There are ways of avoiding that by incorporating things like redundancy so that multiple backup systems have to fail in order for the entire system to fail, and edge cases so that we consider in advance the full range of possibilities, however rare their occurrence may be.

Because we know things will fail, we should design them in a way such that when they fail, lives are protected first and foremost, wherever lives are at risk. In elevators, it would be bad design for them to plummet with the loss of power. Instead, they utilize fail safe design, where power keeps the brakes off and loss of power activates them. They fail into a safe state, ergo "fail safe."

Okay, so what does this have to do with basic income you may be asking?

It's simple. We know that our primary income distribution system fails. It fails all the time. It's called losing your job. We have a "safety net" designed to catch people when it fails, but that system is really poorly designed, and it also fails all the time, at which point, people can and do die as a result.

We have engineered a life support system without fault tolerance, and we did it because engineers didn't design the system. Politicians did. Special interests did. And it's built on antiquated job-centric moralism instead of contemporary life-centric realism.

Realism demands that we recognize human beings need money to live within a system of private property that withholds legal access to basic resources on the condition of having money or qualifying for government assistance. It is mission critical for people to have money to spend on what they need to live. So just make sure they have it, by supplying it to everyone unconditionally.

Here's how UBI would introduce fault tolerance into our life support system we call the economy:

First, everyone starts with the money they need to live. We wouldn't create a life support system on a space station where in order to receive oxygen, one would need to work to obtain it. Life support is life support. Dead people can't work. So make sure people get oxygen so they can stay alive. Living people will do much more work than dead people.

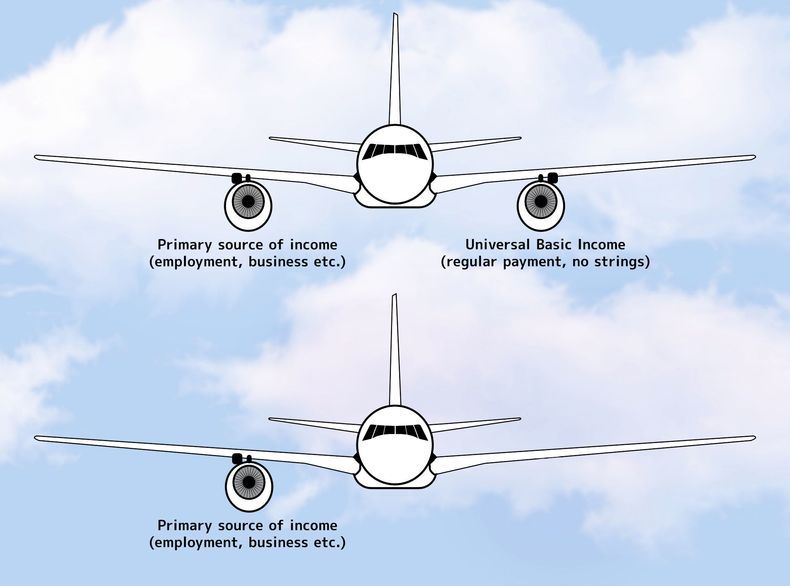

Next, everyone who works for additional money would be utilizing redundancy. They would have two streams of income. If they did multiple jobs or began earning passive income of some kind, it would be multiple streams of income. Instead of a one-engine plane, they could have two or three or more engines keeping them in the air. If one engine was lost, they'd have others, and because of the UBI, they'd never have zero.

Because UBI would mean incomes never fall to zero, anyone who ever loses their job would fall to the level of the UBI instead of the severe poverty of having $0. We can think of this as what engineers call "graceful failure."

Graceful failure means that a failure does not result in catastrophic failure (e.g. sickness or death), and instead fails in a way that protects people or property from injury or damage.

With UBI, people who lose their jobs would fall to a state above the poverty line, meaning that failure would never result in poverty. This builds resilience into the system. People who still have something instead of nothing are more able to get back up again, and find new employment. They're also more likely to take risks, secure in the knowledge that failure won't result in death.

There is a belief we have a safety net that protects all those who lose their jobs. This belief is a myth. It helps some people, but before the pandemic even hit, 13 million people in America were already living in poverty entirely disconnected from all federal assistance programs. The best functioning program is SNAP, which reaches 3 out of 4 people in poverty, and lasts for 3 months every 3 years. The worst is TANF which varies by state, and in Louisiana reaches 4 out of 100 families in poverty. Disability assistance reaches 1 out of every 5 Americans with disabilities, and the average waiting time to qualify is two years. Housing assistance reaches 1 out of every 4 Americans who qualify. Unemployment insurance reaches about 1 out of every 4 unemployed people.

See the pattern? Most of our safety net programs tend to exclude 3 out of every 4 people who need them. Because of UBI's universality, 0 out of every 4 people would be excluded from assistance, because they'd already have it, and many wouldn't even need any additional assistance beyond their UBI, because it would provide more than many existing supports even offer.

This leads me to another engineering element of system design: bang-bang vs. proportional control.

Bang-bang design is like the way thermostats typically work. You set the temperature at what you want, and when the environment gets too far above or below that setting, bang, the air conditioning or heat kicks on to bring the room back to the desired temperature, and then, bang, it turns off again.

Proportional control means that the further a system strays from the desired setting, more force is applied to bring it back. It doesn't wait to do anything until a point is reached. It adjusts at all points.

Right now, our safety net uses bang-bang design. If you lose your job, bang, the safety net turns on, that is if you satisfy the necessary conditions, and you may or may not still fall to your death because of the holes in the net. If you do get help, it's temporary and then, bang, no more help, or if you don't satisfy the conditions, bang, no more help.

However, UBI would be proportional control design. Everyone receives UBI, but everyone also pays for it in varying amounts depending on income and/or consumption. So if your income goes down for any reason, or to any degree, you pay less for your UBI, meaning your disposable income boost is increased. In economic terms, this is called countercyclical fiscal policy. During good times, when most people are employed, you might be paying $1,000/mo in taxes to receive $1,000/mo in UBI, meaning a $0/mo income boost due to earning over six figures. If your hours are cut, you might then pay $500/mo in taxes to receive $1000/mo in UBI, meaning a $500/mo income boost. And if you lost your income entirely, you'd pay $0 in taxes to receive $1,000/mo in UBI, meaning a $1,000/mo income boost.

Thus, UBI would respond proportionally to income loss, creating much more stability in incomes than any bang-bang design could provide. Most biological systems utilize such proportional control, because evolution discovered that it tends to just work best when it comes to life support.

This is the engineering argument for UBI: We are all living, breathing, human beings, and we all need money to obtain the food and housing and everything else we need to stay alive. The best way to make sure we all stay alive then, is to make sure we always have a basic amount of money, and the best way to make sure we always have a basic amount of money is to provide it to everyone at all times, so it's always there, no matter what.

Any argument to the contrary is not sound from an engineering perspective.

Failure is inevitable. There will always be mistakes made. There will always be job loss. There will always be safety net failures. There will always be disasters. There will always be pandemics.

Therefore, we should always have basic income, so that when these things happen, we're less likely to die, and more likely to scrape ourselves off, and get right back up again.

Unconditional basic income is how to engineer resilience into our social and economic systems.

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.