The Science Behind A Christmas Carol

First published in 1843, A Christmas Carol is a timeless story that we have cherished ever since, especially during the holidays. The tale by Charles Dickens has been adapted and re-adapted, modified and satired, with such frequency that we may not even recognize it in all its forms.

So why is it so timeless? Why has it had such a lasting cultural impact? What is it that so strongly connects with us?

The crux of the tale, and the brilliance of Dickens, rests within a single word – empathy.

At its core, A Christmas Carol is the transformation of a man without empathy, to a man with empathy. It accomplishes this through forcing the character Ebenezer Scrooge to remember the past, witness the present, and to consider the future. It is through seeing other human beings as human beings with lives equal in worth to his own, that forms the basis of Scrooge's transformation.

The basis of this need for transformation and how it is accomplished actually has some very interesting science behind it.

The Rich Have Less Empathy

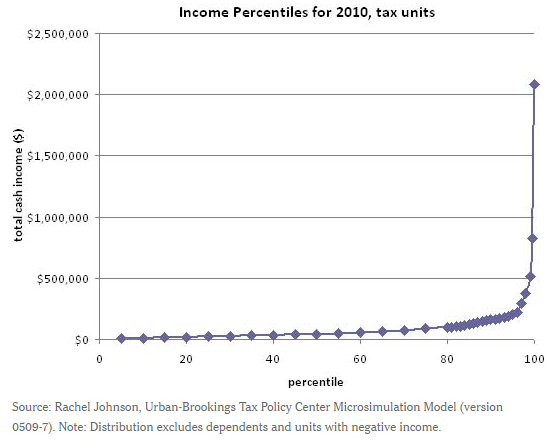

Studies show that as a person grows in wealth, they lose empathy for their fellow man. This is also directly tied in with inequality, because as someone climbs a curve exhibiting exponential growth, that person will have exponentially fewer peers.

When you are among the bottom 95% of earners, you can look around and feel you are surrounded by those who are doing mostly just as well as you are. Maybe a bit better and maybe a bit worse, but for the most part you feel among good company. However, once you enter the top 5% or so, suddenly you can feel poor despite having great wealth. Those at the top have fewer peers around them, and so they end up feeling less connected to those around them, and especially far less connected to those far below them.

One particularly interesting study recently found that higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior and did this through studying drivers and how they behaved according to the price of their car.

The study involved experiments in the real world as well as laboratory scenarios. In the first two experiments, onlookers watched to see whether drivers obeyed traffic laws (and common courtesy); the drivers’ cars were also ranked on a five-point scale, according to prestige, from used Corolla to new Mercedes.

The first test was whether drivers would follow the proper order at a four-way intersection, with stop signs. Nearly 250 were observed. About 8% of the drivers in the lowest tier of prestige broke the rules, compared with 30% in the highest.

The finding was similar when a pedestrian stepped into a crosswalk on a straight stretch of road. In that case, involving 150 drivers, all five of the drivers on the lowest rung of prestige followed the rules—an admittedly small sample. But the proportion of drivers who ignored the pedestrian rose from 29%, in the second tier of prestige, to 46%, in the fifth and highest. -Source

Make a mental note of this experiment and try it yourself. The next time someone cuts you or someone else off, notice what kind of car they are driving. Is it an old beater that looks like it’s barely running, or is it a brand new Mercedes? Science says that odds are, it’s a Mercedes.

This is not to suggest that all Mercedes drivers are assholes, or to somehow demonize the rich as being a different kind of person. This is only to point out how environment impacts behavior, and how the more disconnected someone becomes from the great many, the more they begin to think less of everyone else.

This is the science behind Ebenezer Scrooge and why he is a character that is both the richest in town, and the one with the least empathy for others.

So what is the science behind his transformation?

Empathy Can Be Increased by Thinking of People as People

Studies show that those with less empathy, which again tend to be those with more money, can show greater empathic brain activity by simply being asked to consider what someone’s favorite food might be, instead of what color their skin is.

When our study participants had to place others into a social category—even if it was by age, not race—they saw black faces differently than white faces. But the gray dot exercise showed it was possible for Whites to look at black faces without getting this effect. More important for everyday interactions, when participants were prompted to judge these people as individuals—individuals with their own unique tastes and preferences—they reacted no differently to black faces than they did to white ones. Similarly, my lab’s latest brain scans indicate that people stop dehumanizing homeless people and drug addicts when they’re made to guess what these people would like to eat, as if the study participants were running a soup kitchen.

What this research suggests is that the environment can interact with human nature for good or ill; social conditions can reduce prejudice, just as they can foster or exacerbate it. -Source

Science therefore shows us that those without empathy are not lost causes. Anyone can experience more empathy for others if it is properly fostered. Get people who actively dislike each other and constantly disagree to sit down across the same table, and they can begin to reach agreements by just getting them to ask each other questions that are of a personal nature. A “die hard conservative” can consider themselves to be the mortal enemy of a “tax and spend liberal”, agreeing on nothing and thinking of each other as evil and stupid. And yet get them to talk about their lives with each other, and suddenly even they can start finding common ground.

This is the science behind Scrooge’s transformation. Empathy can be fostered by getting people to think about other people as actual people with actual lives, actual troubles, actual pain, and actual joys. These details need only be learned and considered.

So what is the science behind Scrooge choosing to give away more of his wealth?

Feeling Less Wealthy Drives Support for Redistribution

Scrooge is shown that even though he is financially rich, he is socially poor. He has no friends. He has no one who loves him or would miss him if he died. He is made to recognize he isn’t so rich after all because aside from money there is little else he has. In realizing he has less than he thought, he becomes more willing to give more to others.

Economic inequality in America is at historically high levels. Although most Americans indicate that they would prefer greater equality, redistributive policies aimed at reducing inequality are frequently unpopular. Traditional accounts posit that attitudes toward redistribution are driven by economic self-interest or ideological principles. From a social psychological perspective, however, we expected that subjective comparisons with other people may be a more relevant basis for self-interest than is material wealth. We hypothesized that participants would support redistribution more when they felt low than when they felt high in subjective status, even when actual resources and self-interest were held constant. Moreover, we predicted that people would legitimize these shifts in policy attitudes by appealing selectively to ideological principles concerning fairness. In four studies, we found correlational (Study 1) and experimental (Studies 2–4) evidence that subjective status motivates shifts in support for redistributive policies along with the ideological principles that justify them. -Source

In other words, it is how wealthy we feel, not how wealthy we may actually be, that drives our perspectives on wealth redistribution. If you feel very rich, you are less likely to feel others should have more. The less rich you feel, the more likely you are to feel others should have more.

This is the science behind Scrooge's shift in wanting to keep all of his money for himself, to wanting to share his wealth with those around him.

It is these three areas of contemporary scientific research that exemplify just how ahead of his time Charles Dickens was.

He knew how the wealthiest among us lose empathy for those less wealthy.

He knew how this loss of empathy was not permanent and could be reversed.

He knew that feeling less wealthy could drive the desire to keep less and give more.

A Christmas Carol is a story about the loss of empathy, the gain of empathy, and the act of empathy. Backed by the latest science, Dickens will continue to live on - his recipe for a more empathic society always awaiting rediscovery. This holiday favorite will long remain a lesson ready to be applied to the world around us. The spirit of giving need not exist only once a year. It really can exist within all of us, every day, of every year.

We need only remember our past, witness the present, and consider our future.

Learn more about the science behind this article:

Did you enjoy reading this? Please click the subscribe button and also consider making a monthly pledge in support of my daily advocacy of basic income for all.

_large.jpg)

UBI Guide Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.